Inequality has always been at the heart of the climate crisis. Traditionally, inequality between countries has loomed largest: Rich countries have been responsible for the most greenhouse gas emissions, but poor countries have suffered the most from the extreme heat, drought, storms, and rising seas driven by those emissions. New research highlighted last week in the Guardian, however, suggests that inequality within countries is just as important.

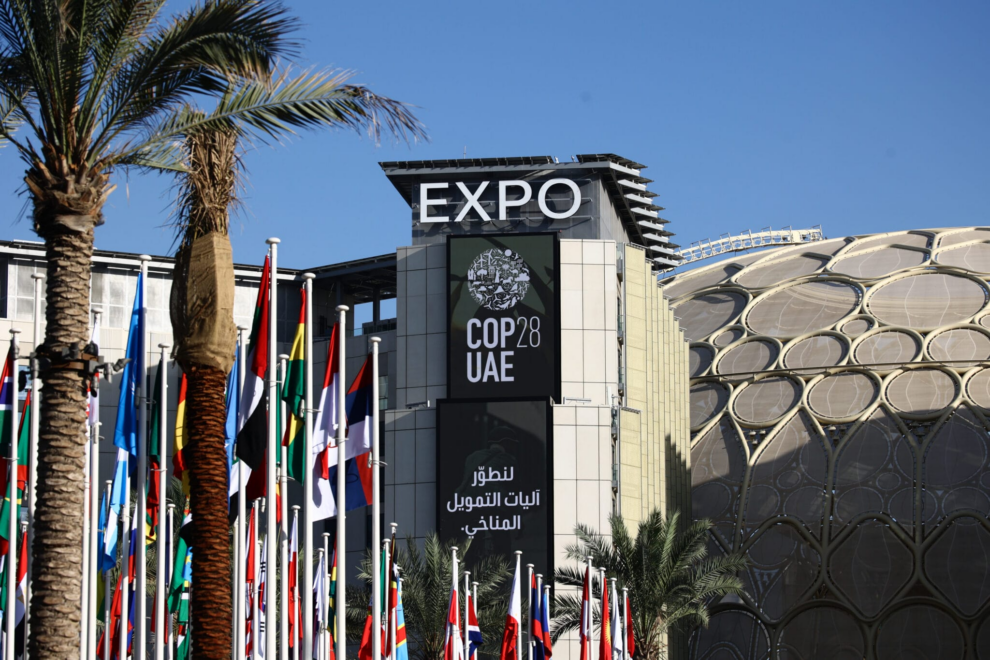

As journalists cover the COP28 negotiations, which began today in Dubai, this twist on inequality is worth our attention. Ignoring the role of inequality within a nation can cause governments to get both the policy and politics of climate action wrong. A salient example? France’s “yellow vest” protests that erupted after President Emmanuel Macron increased taxes on diesel fuel and that forced Macron to retreat.

The Guardian’s “carbon divide” series, published last week, emphasizes that inequality between nations remains vital to tackle too. Rich countries still aren’t delivering on the $100 billion a year they are legally obligated to provide to help poor countries shift to non-carbon energy sources and boost resilience to climate impacts. In a historic development, countries did agree in COP28’s opening hours to launch a “loss and damage” fund to compensate vulnerable countries for climate injuries that cannot be fixed, but the contributions pledged to date from rich countries are “a drop in the ocean compared to the scale of the need,” said Mohamed Adow of the NGO Climate Shift Africa.

“[T]he richest 1% of the [global] population produced as much carbon pollution in one year as the 5 billion people who make up the poorest two-thirds,” the Guardian noted, summarizing the research by Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute. The richest 10% are responsible for 50% of emissions, the poorest 50% for 8% of emissions.

Climate policy will be more effective and less politically fraught if it targets the high-emitting wealthy, Lucas Chancel, a co-director of the World Inequality Lab at the Paris School of Economics, told the Guardian. In the case of the “yellow vests” protests, Chancel said, “There were a lot of households that overall emitted relatively little, but their transport emissions were quite high because they live in rural places, and they had no other option than to use the car. So the carbon tax just meant they had less disposable income — it did not reduce their emissions — and there was a backlash.”

Last week, the Dutch far-right PVV party sailed to victory after stoking populist complaints about migration and climate action’s supposed economic costs. (“We will stop the hysterical reduction in CO2,” the party’s manifesto pledged.) In the US, former president Donald Trump justified withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on similar grounds, and Republicans continue to stoke fears that climate action imposes undue costs on everyday people.

Smarter policy can avoid such backlash. For example, a carbon dividends strategy “puts a price on carbon emissions and returns the money straight to the people,” economist James K. Boyce wrote in Scientific American. “Most households would get more in dividends than they pay in higher fuel prices.” Canada’s carbon tax works much the same way.

“Inequality between people has increasingly become a structural impediment to … climate action,” the Guardian wrote. As such, inequality is something we journalists have to integrate into our understanding and coverage of the climate story, both at COP28 and beyond.

Source : Covering Climate Now

Add Comment